Ritter’s Audiac used white noise and songs in place of anesthetic, claiming to distract patients from any sensations of pain.

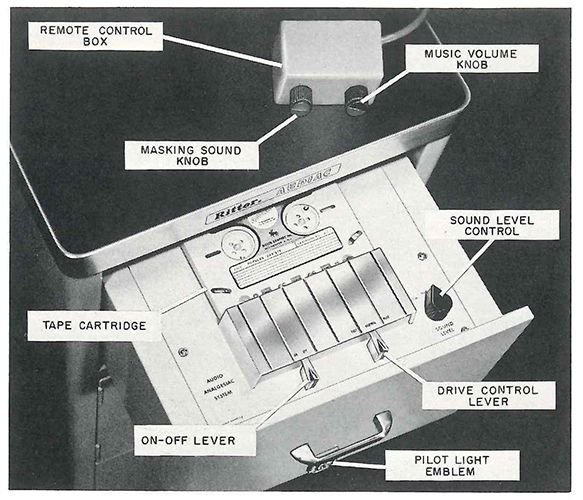

BEHOLD ONE OF dentistry’s colossal flops. Introduced in 1960, the Audiac (short for “Audio Analgesic”) claimed that the right mix of sounds can “swamp or inhibit the original pain sensation,” drowning out handpiece noise in the process. Surprisingly, it was made by Ritter, one of the best dental equipment outfits at the time. The Audiac’s chairside cabinet contained a cassette tape player and white noise generator. Patients were given headphones and a remote volume control to dial the “anesthetic” effect up or down. A second set of headphones allowed doctors to monitor the sound levels.

BEHOLD ONE OF dentistry’s colossal flops. Introduced in 1960, the Audiac (short for “Audio Analgesic”) claimed that the right mix of sounds can “swamp or inhibit the original pain sensation,” drowning out handpiece noise in the process. Surprisingly, it was made by Ritter, one of the best dental equipment outfits at the time. The Audiac’s chairside cabinet contained a cassette tape player and white noise generator. Patients were given headphones and a remote volume control to dial the “anesthetic” effect up or down. A second set of headphones allowed doctors to monitor the sound levels.

Popular Electronics magazine was impressed: “Almost any amount of what might be called ‘dental pain’ can be readily blocked off. And according to doctors, that is exactly what happens.” Except it wasn’t at all what happened. Just ask the mother of one of my longtime employees, who got coaxed into trying the Audiac. The instant the bur touched her tooth, she sternly informed her doctor she’d be opting for an injection instead. As more patients revolted, the Audiac died off. Ritter dismantled the remaining inventory for scrap, selling off the audio equipment inside to electronics stores. That’s why I don’t own an actual Audiac, only some literature about it.

Heavy metal: Think of the Audiac as a 200-pound dental iPod.

Before this moment of mass hysteria ended, six companies—including Cavitron and Phillips—planned to introduce similar devices, according to a 1960 article in Electronics magazine. Tellingly, the same story reported that a skeptical American Dental Association “neither accepted nor rejected” the idea but was studying it. The ADA probably didn’t have to study it for long. Audio analgesia isn’t music to anyone’s ears. ■

LARRY COHEN, Benco Dental’s chairman and chief customer advocate, has over the past half-century collected hundreds of unique dental artifacts, which reside at Benco’s home office in Pittston, Pennsylvania.