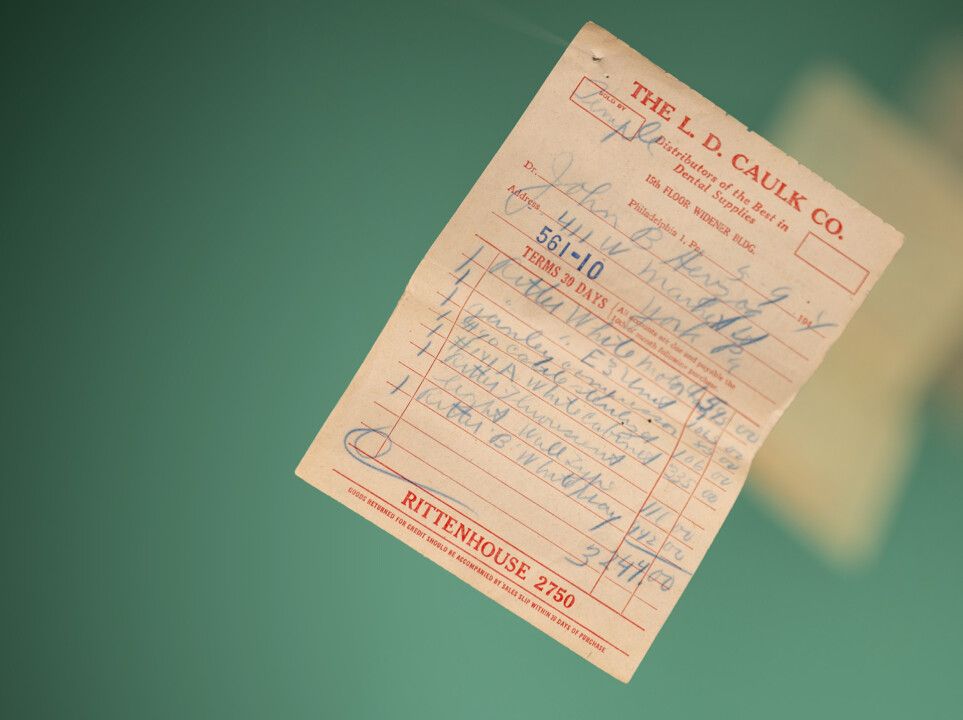

At first glance, this might look like somebody’s restaurant bill, but it’s actually a complete invoice for outfitting a state-of-the-art dental office in 1944.

IT’S AMAZING to think that at one time, you could handwrite all the key components of a dental office on a single invoice the size of a restaurant’s guest check. Granted, this was all the way back in 1944—decades before even the high-speed handpiece was invented. None of us wants to go back to those days, though you can’t help but admire the simplicity of it all.

LARRY COHEN, Benco Dental’s chairman and chief customer advocate, has over the past half-century collected hundreds of unique dental artifacts, which reside at Benco’s home office in Pittston, Pennsylvania.

This particular bill is from L.D. Caulk, which you now know as part of Dentsply. Back then, the company was vertically integrated, manufacturing products and selling them in its own stores. (If memory serves, the government forced many vertical operations like these to divest of their retail components.) As for Dr. Herzog, the customer, it appears he had a good run as a small-town dentist before passing away in 2003. While roughly $3,200 was a lot of money back then—and still is, in my opinion—I’m also sure his equipment paid for itself many times over before it was finally retired. All things considered, it was a small bill to pay for a long career helping patients.