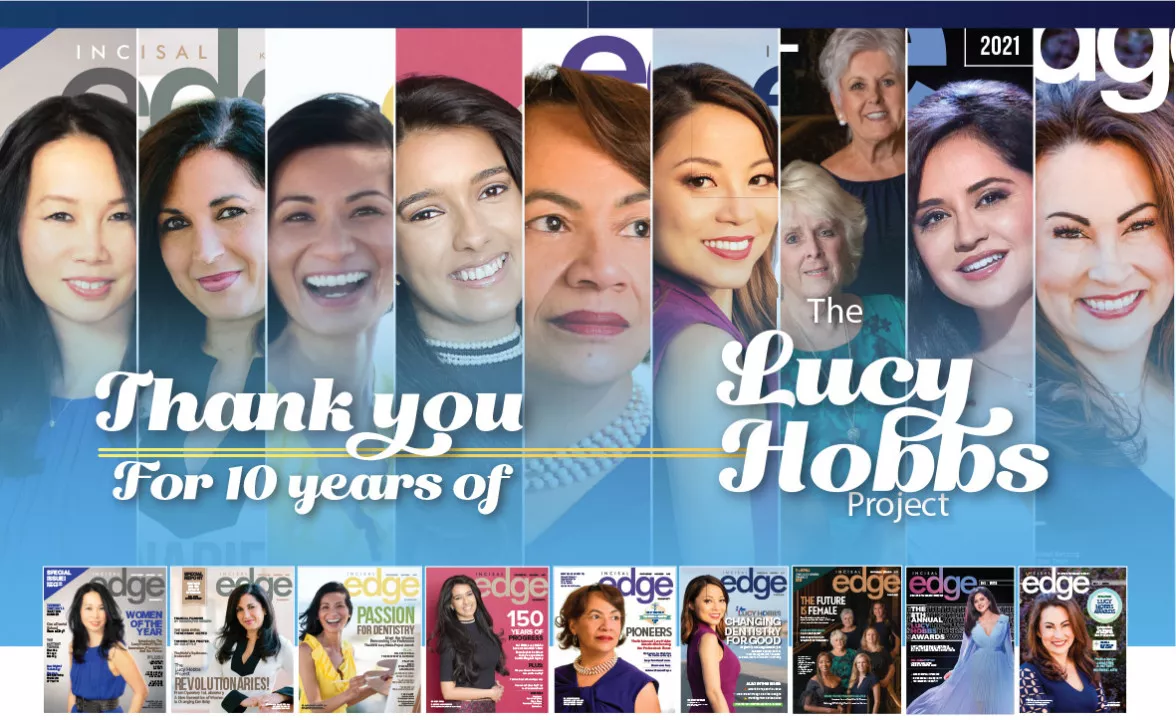

WHEN WE FOUNDED the Lucy Hobbs Project in 2013, we were confident it would take on a life of its own. We didn’t envision that it would be embraced by Hollywood A-listers and award-winning TV news stars. That’s a testament to you and the more than 10,000 members, boosters and honorees who have made the Lucy Hobbs Project—and these annual awards—so memorable. Whether as a participant, follower or simply a reader of Incisal Edge, you’ve all become part of a focused initiative that grew into a small but enormously influential movement.

Inspired by an extraordinary life, the Lucy Hobbs Project pays tribute to the first American woman to earn a dental degree. It’s impossible to know how much health care would have benefited from the influence of all those who were excluded for so long. But we look forward to an ever more exciting future. The unifying force of Lucy Hobbs continues to rally those who believe that empowering women to drive change makes the world a better place.

Ten years after its founding, the Lucy Hobbs Project has honored dozens of women of accomplishment in health care, community service, education, science and business. We’ve celebrated innovation and giving back at unforgettable events across the country, and more great things are on the horizon. Now, 10 years later, we take a look back at the people who joined us, the places we’ve been together, honorees and event speakers, all of whom have made a great impact—on dentistry and beyond.

WHO WAS LUCY HOBBS

WHO WAS LUCY HOBBS

In our inaugural Lucy Hobbs Awards issue (Summer 2013), we published a detailed life history of the awards’ namesake on the assumption that readers might not be familiar with this remarkable woman. Excerpts from that first bio are below.

LUCY HOBBS WAS BORN on March 14, 1833, in a rural outpost in upstate New York that had recently acquired its first road. At the time, dentists were considered little more than “tooth carpenters,” traveling tinkerers for whom pulling teeth was just one of many roadside services provided.

The overall state of dentistry was for a long time of little concern to Hobbs, who was the seventh of 10 children, and just 10 years old when her mother died. As a young girl, she attended school and worked as a seamstress on the side to help her family make ends meet. She was barely 16 when she took a teaching job in Brooklyn, Michigan, and headed to the Midwest.

For the next decade, while she taught, Hobbs studied anatomy and physiology with a local physician and became engrossed in the study of medicine. In 1859, at age 26, she moved to Cincinnati, determined to attend medical school at Eclectic Medical College, which was rumored to consider female applicants. Just months before she applied, however, the school changed its policy.

“There are so many instances where the average psychological constitution would back off or erupt in anger,” says Gina Kauffman, author of More Than Petticoats: Remarkable Kansas Women, which includes a chapter

on Hobbs. “But she was calmly persistent.”

Persistent indeed. Before long, Hobbs prevailed upon a local professor named Charles Cleaveland to resume her private medical training. It was ultimately he who suggested that she consider dentistry instead of medicine. A dentist need not make house calls in all

kinds of weather, he told her. And wouldn’t an office practice be more suitable for a woman?

And so Hobbs pursued dentistry. Because most aspiring students completed an apprenticeship before applying to dental school, she scoured Cincinnati in search of a willing tutor. Invariably, her inquiries were met with reprimand or stern rebuke.

“People were amazed when they learned that a young girl had so far forgotten her womanhood as to want to study dentistry,” Hobbs (referring to herself in the third person) wrote later in The Dental Register. “Nothing daunted, she kept on until nearly every office in the city of Cincinnati, Ohio, was besieged.”

Finally, a dentist named Samuel Wardle agreed to teach Hobbs all he knew. “To him alone belongs the honor of making it possible to enter the profession,” she wrote. “He was to us what Queen Isabella was to Columbus.” For the next few months, Hobbs lived in a small attic room, sewing by night to earn her keep and studying dentistry by day. In March 1861, she applied to the Ohio College of Dental Surgery, whose faculty rejected her by a vote of four to two.

Yet again, Hobbs would not be dissuaded. There were plenty of men practicing dentistry without a diploma, she reasoned; therefore, so would she. The day she turned 28, she opened a small practice on Fourth Street in downtown Cincinnati. Patients were slow to materialize at first, and her weekly earnings often amounted to little more than 25 cents. Then the Civil War broke out. “Business was paralyzed,” she wrote. “A penniless girl could not live where old practitioners failed.”

So Hobbs picked up and moved. Borrowing money from a friend to pay her way, she headed west to Bellevue, Iowa, a village where she opened a second dental office and became known among local Native Americans as “the woman who pulls teeth.” Before long, she had saved enough money to buy her first dental chair and relocate yet again to a thriving Mississippi River town called McGregor.

Hobbs’s reputation grew in Iowa, and so did her funds. By 1862, she had $3,000 to her name and an invitation to attend a meeting of the Iowa Dental Society, at which she became its first female member. “Professional recognition after six years’ struggle was a balm to many old wounds,” she wrote.

In 1865, the dental society invited her to serve as a delegate to a national convention in Chicago, where her colleagues formally demanded that the Ohio College of Dental Surgery finally admit her as a student. The college complied; its faculty voted again, this time promising to accept her provided she reapply. She did so and was accepted, enrolling as a senior on account of her years of professional experience. She received her diploma on February 21, 1866, becoming the first woman in the world to earn a doctorate in dentistry. She remained America’s only female dentist for the next eight years.

“Such is the lone fight of a young girl against the whole world,” she wrote. “Justice comes so slowly.”

Hobbs took her diploma to Chicago, where she opened a new practice and fell in love with a Civil War veteran named James Taylor. The pair married in 1867, and Hobbs taught her new husband to practice dentistry. Before long, the couple moved to Lawrence, Kansas, where they established a joint practice that soon became one of the most successful in the state.

“Everywhere she moved—Cincinnati, Iowa, Chicago, Kansas—a lot of her clientele built up over the novelty about a woman pulling teeth,” says Brittany Keegan, curator and collections manager at the Watkins Community Museum of History in Lawrence, where Hobbs’s dental chair and tools are on display. “She had to have this fortitude to withstand people coming for a spectacle. But she made it work.”

Hobbs and her husband practiced dentistry together until his death in 1886. Afterward, she retired briefly but soon grew bored and began seeing patients again. She worked until October 1910, when she passed away at age 77. She left a substantial legacy for women everywhere, but its acquisition left its mark on her. “There are passages in all lives where it would be well if all books were closed,” she wrote shortly before she died. “Words never explain the heartaches.” —Jesse Newman

Notable Keynotes

INSPIRATION COMES in many flavors, and the Lucy Hobbs Project’s annual galas and networking events have proven that in spades. From the start, this initiative drew big names: The keynote speaker at the first Hobbs event in 2013 was Oscar- and Emmy-winning actress Helen Hunt, who told attendees that her career was inspired by her maternal grandmother—“a single mother who wrote, directed, did voice work and played piano and organ for a live children’s television show on NBC.”

Among the other keynote speakers who have graced Lucy Hobbs events over the years:

Liz Murray was born in the Bronx to cocaine-addicted parents. She later went, as a documentary about her was titled, From Homeless to Harvard. “When I was homeless,” she told Incisal Edge, “whether I slept on my friend’s floor or in a hallway or in Central Park under the stars, I still had the ability to close my eyes, connect my heart and dream of a better life. The Lucy Hobbs Project is all about celebrating that same bold, visionary gusto in women.”

Carey Lohrenz, America’s first female F-14 pilot, who told attendees to “get comfortable with being uncomfortable. Courage isn’t comfortable; courage means breaking out of your comfort zone.”

Libby Gill, who gave up a corporate career to start her own coaching and consulting firm. “We need to let women know that they’ve got this,” she said. “To give them tools and strategies they can put into action. What the Lucy Hobbs Project does is tell women we’re shaking things up.”

Robyn Benincasa, a former firefighter and world-record kayaker. “Women at the top of any industry aren’t trying to be men,” she said. “They’re trying to use their core strengths and talents to succeed. The road might be different, but the finish line is the same.”

Erin Gruwell, who in the early 1990s transformed a group of 150 “hopeless” high schoolers in Long Beach, California, into passionate writers, all of whom would end up graduating. A movie about them, The Freedom Writers, was released to acclaim in 2007. She spoke about the power

of orthodontics: “The one thing I hear the most, especially from incarcerated kids, is the power of a smile. It humanizes a room and warms people’s souls. I smile all the time.”

Poppy Harlow, an Emmy-nominated journalist who is an anchor at CNN This Morning. Her keynote occurred at the 2019 event in Chicago, whose three days were dedicated to two themes: “Mind+Body+Soul” and “Achieving Your Personal Best Balance, at Home and Work.”

Straight From the Source

Dr. Sara

Krout, the first female dentist in the U.S. armed forces

THE INAUGURAL Lucy Hobbs issue of Incisal Edge, in 2013, included what is surely the only oral history ever assembled about women in dentistry, from 1900

to the present day. Some excerpts:

Henriette Hirschfeld, one of the country’s preeminent female dentists in the late 1800s: “One afternoon in 1867, I went to the offices of Dr. James Truman in Philadelphia and asked to see him at once. When he appeared and asked me for what purpose I had come, I informed him that I very much wished to enter the Pennsylvania College of Dental Surgery as soon as was practicable. The look of shock that crossed his features

I am scarcely able to describe.”

Dr. Henriette Hirschfeld, early 1900s;

Shannon O’Dell, director and curator of the Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry at the University of Michigan: “Women had demonstrated their abilities in two world wars, yet it wasn’t until 1949 that the military fully allowed women dentists to serve.”

Sara Krout, a Latvian immigrant who was the first female dentist in the U.S. armed forces: “I wasn’t trying to be a pioneer as a woman. As far as I knew, that’s what good citizens did: volunteered.”

“I wasn’t trying to be a pioneer as a woman. As far as I knew, that’s what good citizens did: volunteered.”

—Sara Krout

Dr. Krout with fellow Navy sailors

Shannon O’Dell: “In the early 1970s, there were a host of new federal incentives intended to make sure that women were allowed to apply and be accepted to programs. There was an increase in women going to dental schools, because [the schools] actually went out and tried to get them to apply.”

Dr. Marsha Adler Gordon, a pediatric dentist in Allentown, Pennsylvania, who entered dental school in 1974 as one of 10 women in a class of 550: “The professors didn’t know what to do with us. We unearthed a little black book that a professor kept. It was our grade sheet, and next to all the names of women were little ‘female’ signs!”

Dr. Bonita Neighbors, who grew up in segregated North Carolina and later spent 23 years as the dental director for a region of the Michigan Department of Corrections. She entered dental school in 1986: “There were 12 or 13 women in my entire class. So I was definitely unusual, and I think the fact that I was black was even more unusual. At the time, my husband was a new professor. I had many profs who would say, right to my face, ‘Why are you taking a man’s spot? I heard your husband is a Ph.D.’ ”

Dr. Eugenia Roberts, a general and cosmetic dentist in Cincinnati: “Dentistry is a woman’s profession. It’s part engineering, but it’s also art.”

Dr. Danielle Riordan, a general dentist in St. Peters, Missouri: “In a word, I feel gratitude. It’s a big thing that women came into a field so dominated by men. I get really excited that someone took those steps, because I don’t know if I would have had the courage to do so.”

Sara Krout: “When the Navy had its 200th anniversary, I went to the party. I was proud that I could still fit into my old uniform, and even prouder that they saw fit to honor me that day. I like to think that after all those years, I was just too tough to ignore.” —Elizabeth Dilts

Dentistry’s Mt. Rushmore

OVER THE DECADE that the Lucy Hobbs Project has been celebrating women in dentistry, we’ve lauded some major industry figures. Among them:

• In our summer 2014 issue, we honored the late Joan Austin, who had died in June 2013 at 81. Austin and her husband, Ken, cofounded A-dec in 1964 and built it into an industry colossus. We posthumously bestowed upon Austin our Industry Leader Award in recognition of her life’s work, as well as her philanthropic largesse.

• A year later, we gave Dr. Esther Wilkins the same honor (renamed the Industry Icon Award). Dr. Wilkins was widely regarded as the leading exponent of the practice of dental hygiene, and we sat down with her in her office at Tufts University to photograph her with the eleventh edition of her classic textbook, Clinical Practice of the Dental Hygienist. In 2022, Tufts dedicated a new hygiene clinic in the name of Dr. Wilkins, who died in 2016, three days after her 100th birthday. (See “Honoring a Legend,” page 8.)

• The cover star of our 2017 issue was Dr. Winifred Booker, who took home our Humanitarian Award in recognition of (among much else) her “Lessons in a Lunchbox” program, which we noted had “sent more than 45,000 tangerine-colored lunch boxes to first- through third-grade students in nearly every state. . . . Each lunch box contains Dr. Booker’s patented Dental Care in a Carrot, an orange container designed to store a toothbrush; Silly Strawberry toothpaste; Tutti Frutti dental floss and a rinse cup.”

• Winner of that same Humanitarian Award in 2019 was Dr. Sharon K. Parsons, a general dentist in Bexley, Ohio, whose son passed away in 2015 after struggling with opioid addiction for years. In the wake of his death, Dr. Parsons lobbied the Ohio Dental Association to take action on opioid overprescription—and missed that year’s Lucy Hobbs Project gala because she was attending the bill’s passage back in Ohio.

• In 2021, we gave the Industry Icon Award to Dr. Rella Christensen, who alongside her husband, Gordon, founded the renowned Clinical Research Associates Foundation in 1976—and the couple are still going strong 46-plus years later. “There might be a perception that dentistry isn’t as exciting as it used to be, but the truth is it’s more exciting than ever,” she told us. “With all the new electronics and new ways to diagnose and treat, it’s an exciting time to be in health care in general, [and] in dentistry in particular.”

The Unsung Heroes

HYGIENISTS HAVE long been an overlooked force in dentistry—the unsung heroes who toil in the trenches while the presiding doctors get most of the glory. Over the years we’ve sought to tilt the balance of attention a little bit by noting the contributions of these critical healers. We kicked it off in the first Lucy Hobbs issue, from 2013, noting that in June of that year the American Dental Hygienists’ Association would be hosting a weeklong conference in Boston, “100 Years of Dental Hygiene.”

Among the hygiene history we unearthed:

• Hygienists were initially known as “dental nurses.” In the early 1900s, a Bridgeport, Connecticut, dentist named Alfred Fones trained his assistant, Irene Newman, in the arts of scaling and polishing teeth. She disliked the term “dental nurse,” however, so Fones changed it to the term we know and use today.

• We reported on a then-current survey of hygienists by oral-health conglomerate Sunstar that found “a dedicated and largely satisfied cohort,” with seven hygienists in 10 saying they loved their job.

• A year later, in the 2014 edition of the Lucy Hobbs Awards, we gave the Clinical Expertise Award to Katti Webb Simpson, a hygienist in Maine, the first hygienist we had honored as part of the Lucy Hobbs Project. (Simpson has since been a regular in our pages for a number of reasons, most of which have to do with her professional skills and philanthropic work.)

• We boosted our efforts further in 2015 with “Team Clean,” a full feature consisting of Q&A’s with five hygienists around the country, asking what first drew them to the profession, hurdles they’ve had to overcome, their outside interests and more. Judy Gelinas, then the director of community oral health initiatives at St. Christopher’s Hospital for Children in Philadelphia, put it succinctly: “Dentists restore oral health; hygienists are prevention specialists.”

• Finally, we took a further step forward in 2022: After a nationwide nomination process, we named Shanda Christal-Scott, who works in Providence, Rhode Island, our inaugural “Hygienist of the Year,” which is now an annual award. “All our patients are human beings,” she told Incisal Edge. “If you truly want to help the underserved, you have to rid yourself of bias, never judge, be patient and really get to know people.” Spoken like a true healer.

If you truly want to help the underserved, you have to rid yourself of bias, never judge, be patient and really get to know people.”

—Shanda Christal-Scott Hygienist of the Year, 2022

Male Call

THE LUCY HOBBS PROJECT was designed from day one to celebrate the contributions of women to the profession. Yet we’ve deviated from the distaff periodically over the years, several times giving the annual Trailblazer Award to a male Benco Dental staffer who went above and beyond in the previous year to contribute to a Lucy Hobbs initiative.

We also went a little deeper on one occasion, the 2015 Lucy Hobbs issue, when we looked at the emergence of what we called “The New Dental Husband,” profiling three couples in which the woman is the dentist supported by her spouse in a variety of capacities. Excerpts:

• “In this professional partnership, Dr. Amy Case and Dr. Brian Case decided Amy would initially be out front. She’s the primary dentist at their practice in Cleburne, Texas, while Brian works four days a week elsewhere as an associate, which helps pay down debt and generate

a predictable income stream while they build their own patient base.”

• “While Abel Planas fills in as a dental assistant at the couple’s Naples, Florida, practice, his job is to indulge his love of numbers as office manager. ‘I’m the dentist,’ says his wife, Kenia. ‘He takes care of everything else.’ ”

• “When Drs. Marielaina and Gregg Perrone’s daughter, Ashley, was born, Gregg transitioned seamlessly to the role of a stay-at-home dad. ‘My parents thought it was a little odd, since the man is supposed to be the breadwinner,’ Gregg says. ‘It works for us.’ To ease the transition, Gregg brought Ashley to Marielaina’s Las Vegas office for lunch and a family trip to the park every day.”

One Hundred Years of the AAWD

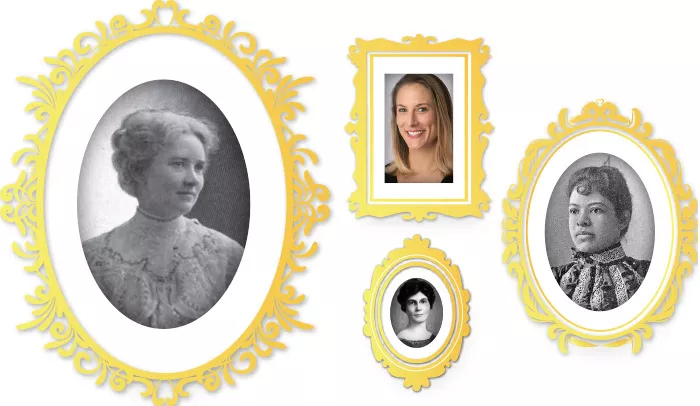

(Clockwise from far left) Dr. M. Evangeline Jordan, Dr. Brittany Bergeron, Dr. Ida Gray Johnson and Dr. Gillette Hayden

IN THE 2022 Lucy Hobbs Project special issue, we looked at the history and influence of the American Association of Women Dentists, the professional organization that had celebrated its centenary at the end of 2021. Some excerpts:

On March 4, 1893, Dr. Annie T. Focht, secretary of the Women’s Dental Association of the United States, issued a report noting that the organization’s membership ranks had grown to 32 dentists in the year since its founding, describing the group as “a society by which [women] could strengthen themselves by trying to help one another.”

The WDA spent the next three decades making fitful but substantial progress for the interests of women in the profession. Then, in 1921, a dozen female dentists, in Milwaukee for the annual meeting of the American Dental Association, founded the Federation of Women Dentists as a sort of successor organization. Two name changes and 100 years later, the American Association of Women Dentists continues to advocate for the interests of female dental professionals at every stage “from dental school through retirement,” as the group puts it.

“The founding mothers, women of stature in dentistry, never intended for AAWD to foster separation of women from men, nor did they

wish to cause fragmentation in the profession,” says Dr. Lauren Aguilar, the AAWD’s president-elect. “These women were involved and respected at all levels of organized dentistry. They wanted a support organization to share their common interests and to enjoy friendships and camaraderie.”

We’re an organization by women, for women.”

—Dr. Brittany Bergeron

Consider the Federation of Women Dentists’ first president: Dr. M. Evangeline Jordan, following three decades later in Lucy Hobbs’s footsteps, was an 1898 graduate of the University of California School of Dentistry (now the University of California San Francisco School of Dentistry). Considered one of the founders of pedodontics, Dr. Jordan was one of the first known clinicians to limit her practice to the treatment of children.

The organization’s third leader, Dr. Gillette Hayden, was a 1902 graduate of The Ohio State University and would go on to found the American Academy of Periodontology in 1914 with Dr. Grace R. Spaulding, the sixth president of what would become the AAWD.

The group’s past members include Dr. Ida Gray Johnson, the United States’ first black female dentist, among many others. “While there are other niche groups for women dentists,” Dr. Aguilar says, “none have the historical backbone of the AAWD.”

Dr. Brittany Bergeron, a cosmetic dentist in Towson, Maryland, served as the AAWD’s president in 2019 and is now in charge of the organization’s corporate-relations efforts. Part of what keeps the group’s influence strong, she observes, is its emphasis on a united front. “Numbers matter,” Dr. Bergeron says. “Organized dentistry is relevant if we want to be able to influence decision making as it affects our industry. We need to work together to have a voice and a seat at the table to have our input and opinions considered.”

“We’re an organization by women, for women,” Dr. Bergeron says. She cautions against reading too much into bare statistics such as the male-female breakdown of dental-school students, significant though those gains are. “Although the gender composition of U.S. dentists has changed dramatically in the last 20 years, there’s not much else that has,” she says. “Dental equipment is still designed for male bodies, journal ads are still aimed at a male audience and local dental meetings are still very much male territory.”

She adds, though, that “I see [the AAWD] becoming even more relevant than it has been in the past. The demographic we represent is increasing. My hope is that these young grads and leaders find their voice in AAWD to ensure its existence for another 100 years.”

That, in the end, is the AAWD ethos. As more women make the dental practice their professional home, the group’s profile and influence will surely only grow. Its extraordinary roster of past presidents and members—to say nothing of Lucy Hobbs herself—would no doubt be beaming with astonishment, satisfaction and pride. —Megan O’Donnell

Forging The Future

WHILE THE FOCUS of each Lucy Hobbs issue, justifiably, is that year’s six primary honorees, we also like to shine a light on other women making a difference in dentistry. Our 2021 Lucy Hobbs issue included a feature, “Inspiring Minds,” showcasing six notables working to drive dentistry forward. Among them:

• Cherie Le Penske, whose Armor Dental pivoted quickly at the outset of the pandemic, raising $1 million in just six days to create Armor Respiration, which made what we called “a hybrid of the N95 mask, a face shield and a sophisticated ventilation system.”

• Katti Webb Simpson, super-hygienist, who had opened a mobile hygiene unit three years prior, then shuttered her stand-alone office during the pandemic to focus exclusively on mobile care—a major benefit

in a large, sparsely populated state like Maine.

• Lisa Fitch and Laura Borst, the leaders of Give Back a Smile, the American Academy of Cosmetic Dentistry program that works with survivors of domestic and/or sexual abuse who have suffered dental injuries, pairing them with doctors who donate their time to restore these women’s smiles.

• Kajuana Farrey Sutton (who would go on to be honored with the Clinical Expert Award in 2022), who in 2009 became the first African-American female dentist in the United States to cofound a dental community health center.

• Linda Niessen, the founding dean of the Kansas City University College of Dental Medicine in Joplin, Missouri.